November 12, 2022

The scope of my initial neighborhood research was rather limited: house histories for the 5000 W. Berteau block only.

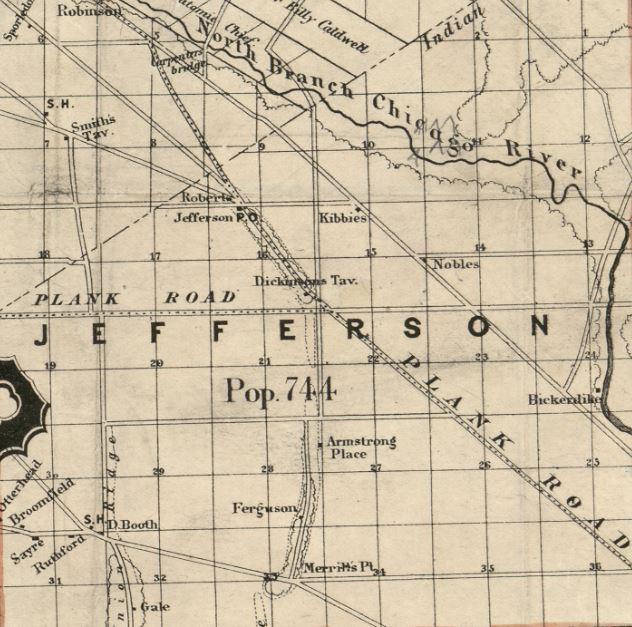

Then the scope started to expand to adjacent blocks – Lawler and Leclaire. And then it spread to farther blocks – basically, the blocks that are primarily comprised of single family homes, built on land that belonged to the Dickinson family.

Inevitably, the scope also expanded to include research about the history of the Dickinson family. Having located the history book, The History of Cook County Illinois (Goodspeed, 1909), which contains a short section (click here to view) with basic facts about Chester Dickinson and Arthur W. Dickinson, I found myself asking more questions:

- Why did Chester Dickinson leave Amherst, MA and come to Cook County?

- How did Chester get here? What was the journey like?

- Why did he settle in Jefferson?

- Who did he buy the land from? How did he know who owned it?

- Where did he go to buy the land?

- How much did the land cost and how could Chester afford it?

- Are original land records readily available somewhere? Where?

And each question leads to more questions….mainly very basic questions about the LAND.

The Land is forever

Before there were houses, subdivisions, streets, etc. there was only the LAND. Clearly, the land is a prerequisite for building anything. Even if our house gets torn down, the roughly 4000 sq. ft. of earth we own under our feet remains. So, let’s switch focus from the history of our houses to the history of our actual land. Here is what I learned …..

United states territories and public lands after independence

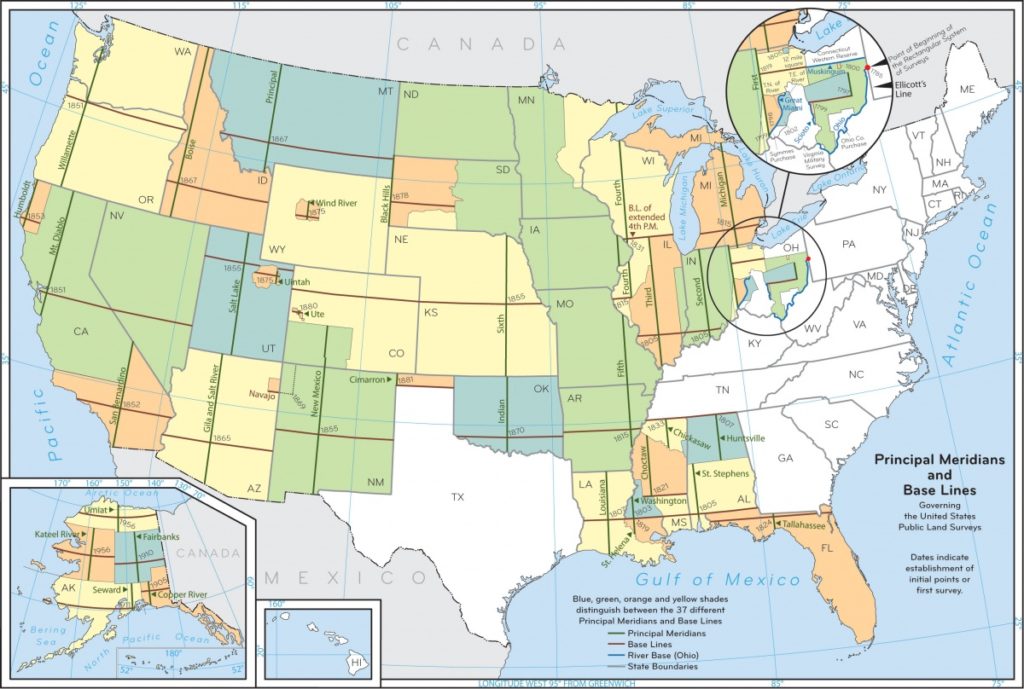

As the United States acquired territories and land, a method and process needed to be developed to manage the tracking and sales of these public lands by the federal government. Therefore, the Land Ordinance of 1785 was enacted (with subsequent revisions over time). The primary element of the Ordinance stipulated that all public lands were required to be surveyed using a standard system before they could be sold, distributed or opened for settlement. The system developed was called the Public Land Survey System (PLSS).

PLSS description

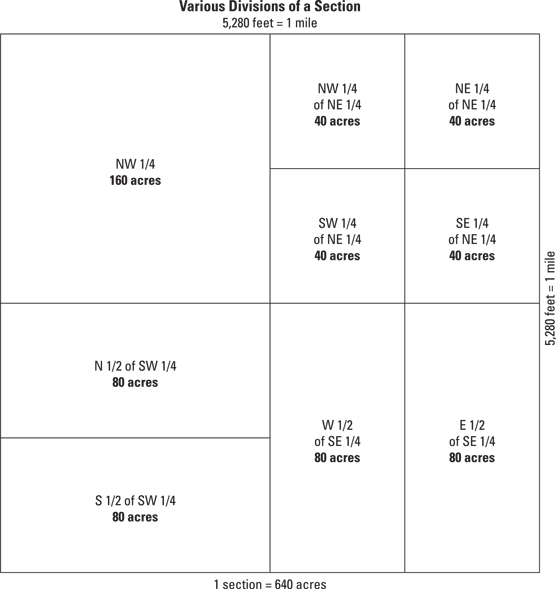

The rectangular coordinate system of surveys divided land into 36-square mile townships (6 miles x 6 miles) and then each township was subsequently divided into 36 square mile sections (640 acres each). Each section is further subdivided into quarter sections, half-quarter sections, or quarter-quarter sections. It should be noted that the survey townships were known as congressional or government townships and not related or to be confused with municipal or civil townships. When surveys began in the area of southern Illinois in 1805, Illinois was not a state yet. And when our area of Illinois was surveyed in 1834, the town of Jefferson still did not exist.

The existence of section lines made property descriptions far more straightforward than the old British metes and bounds system (see sample at the end of this page). The establishment of standard east-west and north-south lines (“township” and “range lines”) meant that deeds could be written without regard to temporary terrain features such as trees, piles of rocks, fences, and the like, and be worded in the style such as “Lying and being in Township 4 North; Range 7 West; and being the northwest quadrant of the southwest quadrant of said section”.

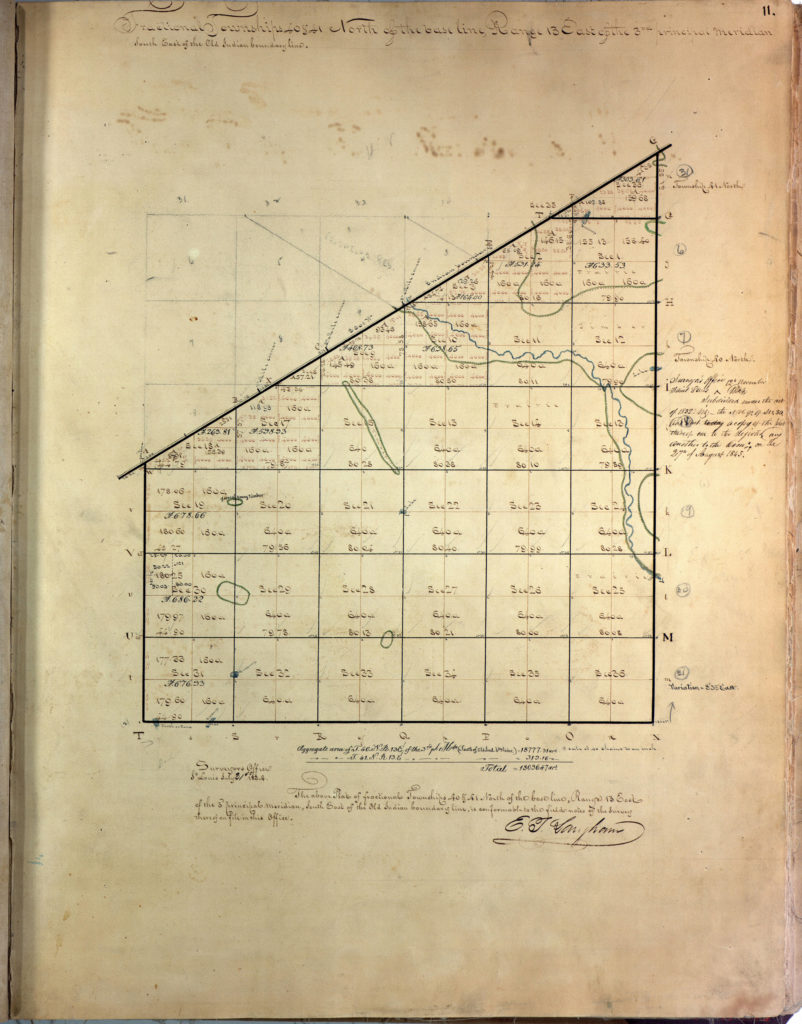

Below is the original survey for “our neck of the woods”. You’ll notice that there are no mentions of a state, a county, a city, etc. since those were probably non-existent nor relevant for purposes of the survey.

It’s hard to imagine, but pretty much the entire land in the US (with some exceptions) was surveyed using this standard grid based system, and the numbering designations are still in use today. Below is a current map indicating the areas of the US where the PLSS was applied.

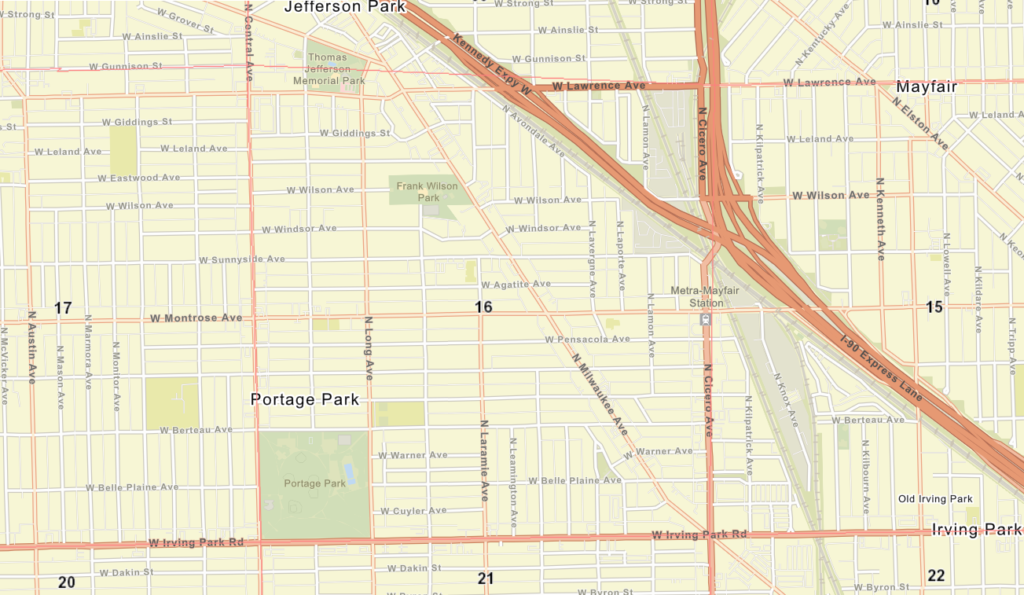

The borders of sections have clearly influenced the location of subsequent streets and roads.

why does this matter?

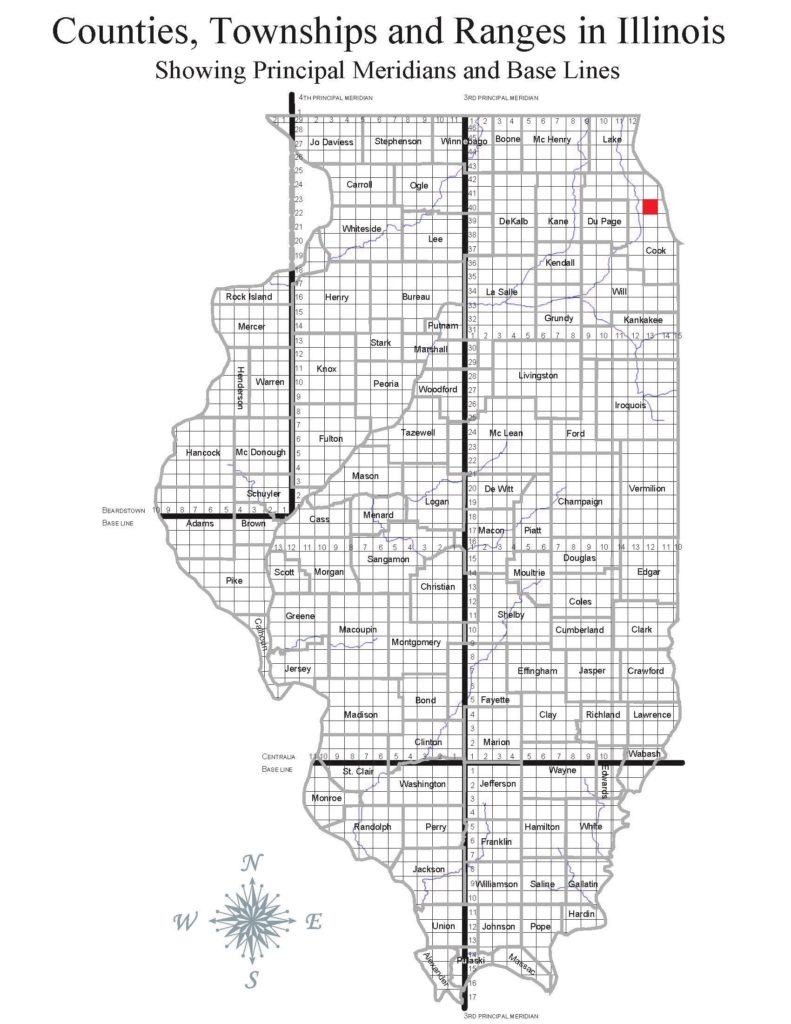

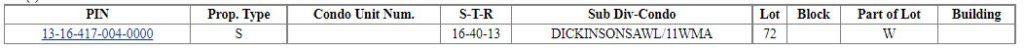

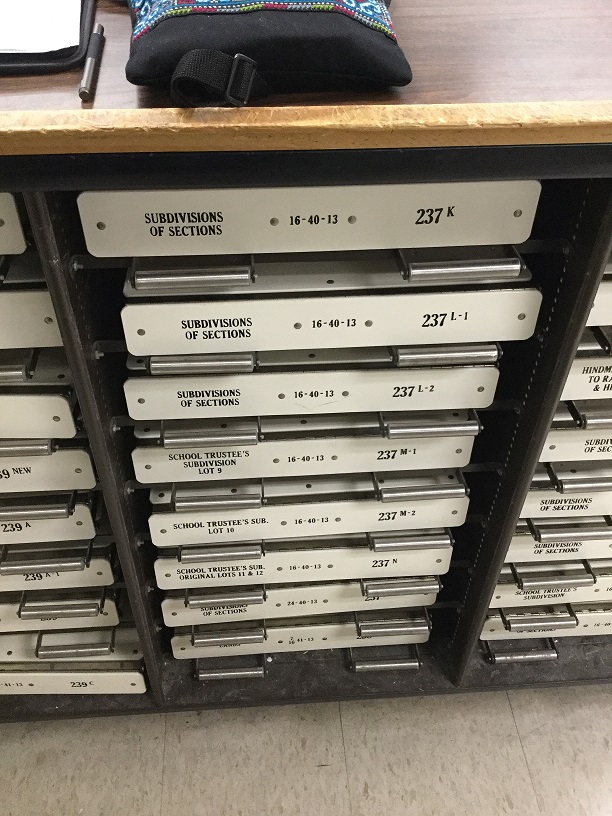

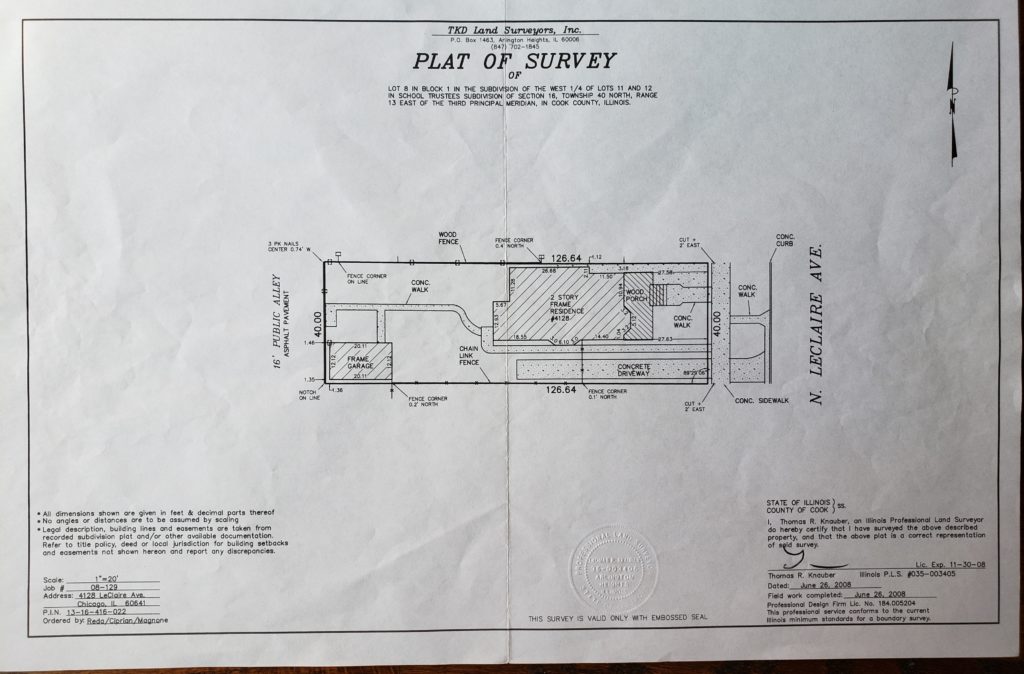

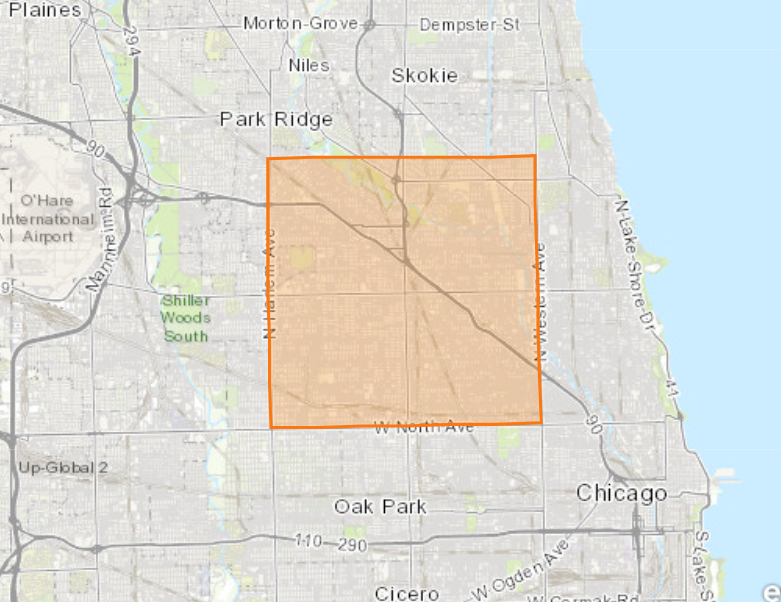

As a property owner, the legal description of your property matters. Every single neighbor’s property documents, such as mortgage, warranty deed, survey, etc. will contain the following somewhere in the legal description: Section 16, Township 40 North, Range 13 East of the 3rd Principal Meridian. This legal description has not changed for over 200 years since established, and probably will never change. It pinpoints the exact square mile that your property is located on in the United States. Perhaps you have seen this on your property docs and did not know what it means. Now you do.

Why aren’t street addresses used in the legal description of property? A street address is not necessarily a fixed, unchangeable designation, and is applied to structures, but cannot be applied to land. Example: 4156 N. Leamington later became 5135 W. Berteau, but the legal description of the lot is the same as before.

From a research standpoint, whether historical or current property research, understanding this designation is essential for finding information. Had I not learned about this, I would not have been able to find the information I found. And when I look at historic or even current real estate maps, and I see this grid with numbers, I now know what those numbers mean.

Armed with this information, I was able to try to start answering some of the questions raised at the beginning of this article. I’ll share those answers with you in upcoming articles.

Sidebar

Learned a good new vocabulary word: boustrophedonic: from left to right and then right to left (mostly associated with a system or writing but can be used as follows: Farmers usually plow their fields boustrophedonically).

“Every township is divided into 36 sections, each usually 1 mile (1.6 km) square. Sections are numbered boustrophedonically within townships as follows (north at top):”

Additional Information and Resources related to U.S. Public Lands

- Public Lands History and Timeline – US Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management. Concise and informative timeline. Worth looking at.

- Land Ordinance of 1785 – Wikipedia

- Public Land Survey System – Wikipedia

- Metes and Bounds vs Public Lands – Virtual Museum of Surveying

- A History of the Rectangular Survey System – Bureau of Land Management. Extremely detailed PDF of a 776 page document published in 1902. For those who are really, really interested in minute details.

Sample Metes and Bounds legal description

“Beginning at a stone on the Bank of Doe River, at a point where the highway from A. to B. crosses said river; thence 40 degrees North of West 100 rods to a large stump; then 10 degrees North of West 90 rods; thence 15 degrees West of North 80 rods to an oak tree; then due East 150 rods to the highway; thence following the course of the highway 50 rods due North; then 5 degrees North of East 90 rods; thence 45 degrees of South 60 rods; thence 10 degrees North of East 200 rods to the Doe River; thence following the course of the river Southwesterly to the place of beginning.”

What happens when the stone gets washed away or the stump rots?

Wow! A lot of information! Very interesting and educational, for me, whos lots in PR are described as: “land ubicated on the north, from the mango tree to the avocado tree” …..

So, both trees, mango and old avocado were destroyed by Hurricane María and no longer exist.

I was wondering if I should plant new trees……

Nonetheless, I love the way specific descriptions are made in the USA…. No fights with the neighbors….

Thank you, Ruta. You’re always so inquisitive! I love it!

Lilly

Maybe you can expand the size of your property by planting the new trees in new spots 🙂

Good idea!😀😀

Great start! None of us knows this stuff, it literally is never taught anywhere.

I’ve noticed those tree lines on the other maps and it’s clear that most of the tree lines are on small humps of land that ran through this original prairie and swamp property. The first roads were built in these humps because the soil was more stable and the roads would stay dry without having to build them up. That’s why Milwaukee (originally “Plank Road”) was located here.

Thanks Ruta!

Always interesting to learn more of your “excavating”!

This was very interesting. Thanks for sharing it.