December 1, 2022

Being an amateur, I’m learning that research is a never-ending rabbit hole. Every piece of information found opens a whole new can of worms and raises a whole new set of questions. These are challenges that I am compelled to pursue, and quite frankly, I do enjoy the quest for the holy grail. But, enough of the bad metaphors.

In the first installment of The Land series of articles, I raised the following questions:

- Why did Chester Dickinson leave Amherst, MA and come to Cook County?

- How did Chester get here? What was the journey like?

- Why did Chester settle in Jefferson?

- Who did he buy the land from? How did he know who owned it?

- Where did he go to buy the land?

- How much did the land cost and how could Chester afford it?

- Are original land records readily available somewhere? Where?

In this second installment of The Land series, I believe I can answer the questions in blue. The grey questions will be answered in future installments, I think (I hope!)

The problem with the questions in blue is that they are mainly Why or How questions, which are usually not addressed in fact-focused history books and articles. Though I wanted to find the answers, I didn’t think there was much hope — until I met the living Dickinson clan. Never did I imagine that they had a treasure, a treasure which they have shared with us…

Alida’s memoirs

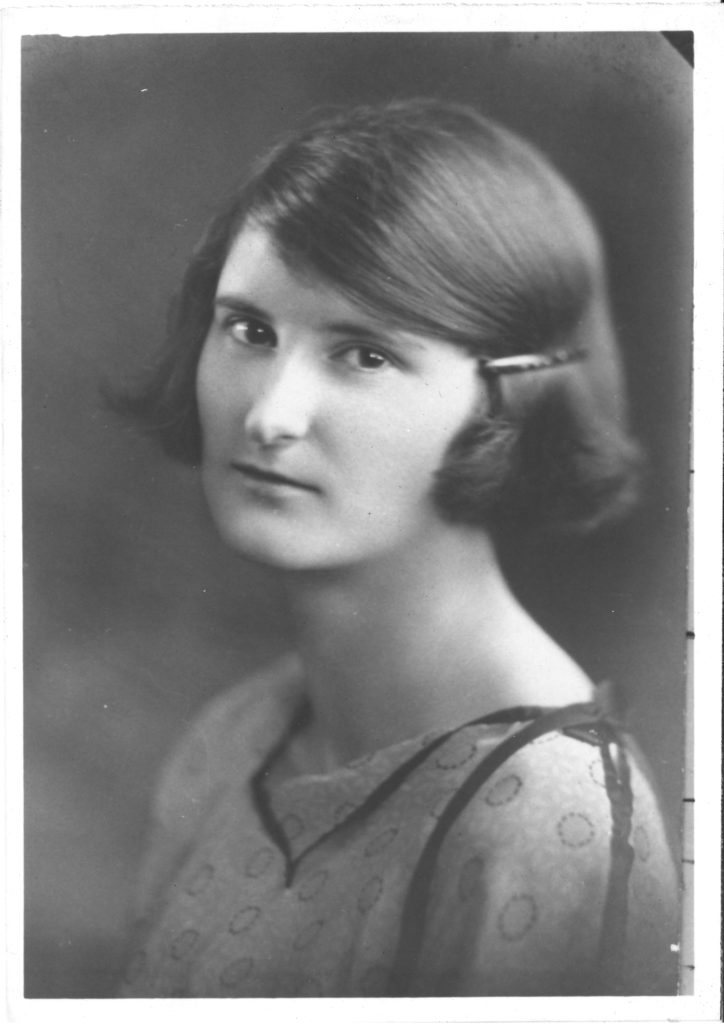

Alida Harriet Dickinson Scharf,

1904-1992

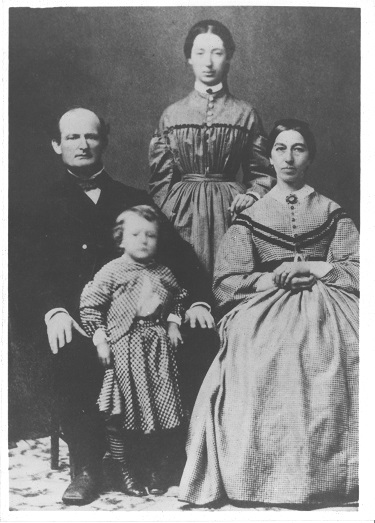

Alida Dickinson was Arthur W. Dickinson’s third child, born in 1904. In 1967, at the age of 63, she began to write her family memoirs and continued writing until 1988.

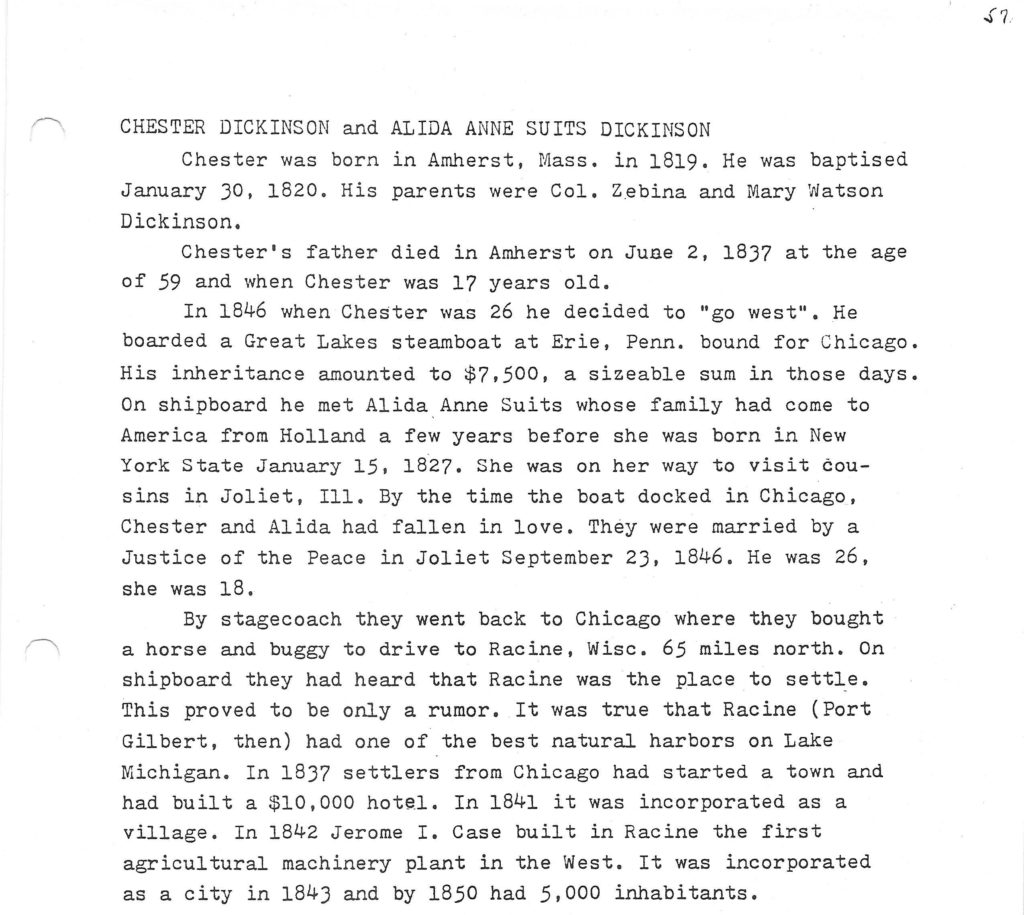

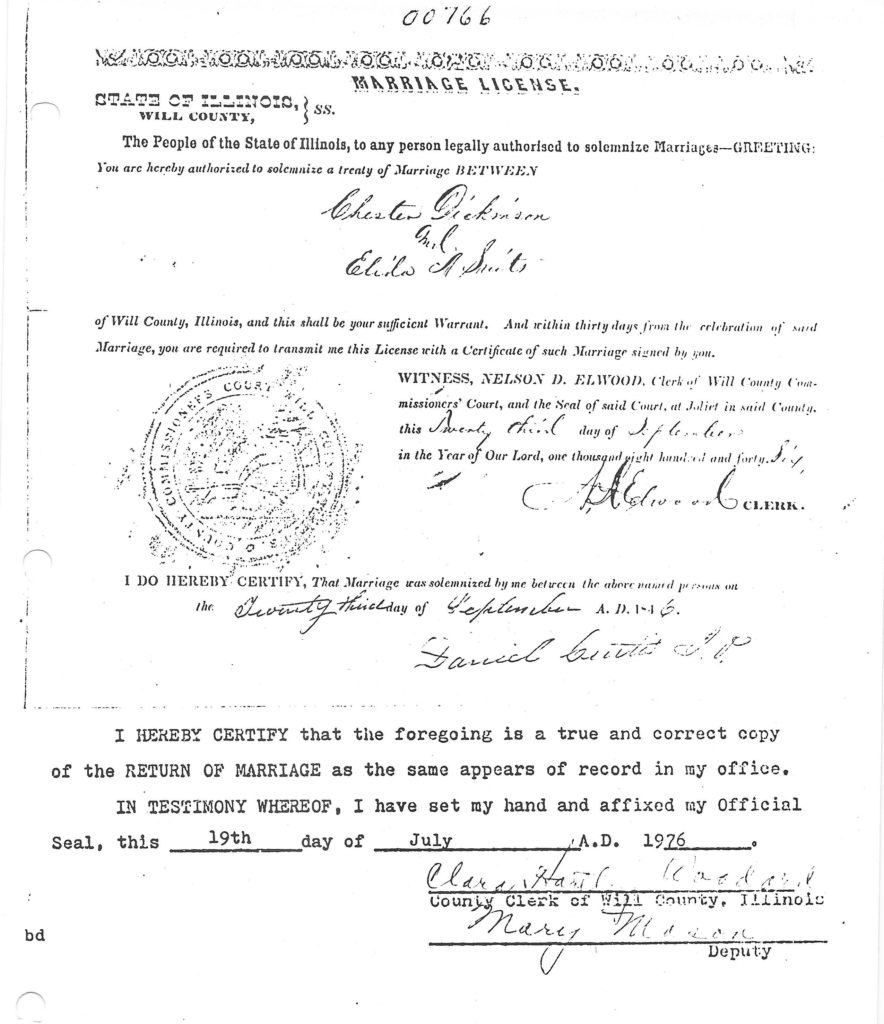

Alida’s grandson, Bennett, very, very generously scanned and shared relevant portions of her memoir with us, providing us with invaluable insights unattainable anywhere else. Below is a portion related to the early history of Chester Dickinson, Arthur W. Dickinson’s father, before and shortly after his arrival to the Chicago area in 1846.

Chester’s journey west

- Why did Chester Dickinson leave Amherst, MA and come to Cook County?

Alida’s Memoir does not offer a specific answer to this question, but generally, various reasons inspired people to expand westward in the 19th century, though two reasons were generally cited more than others. Economic opportunity, or the chance to strike it rich, was the first. The second was a chance at social mobility and progress, which was also tied to monetary desires. Or, for many, the colonies were becoming too crowded and inhabited. Besides that, the rocky soil in New England was not great for farming.

The Northwest Territory—which later would become the states of Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Illinois and Wisconsin—had timber, minerals, furs and fertile land for farming, but the Appalachian Mountains stood in the way — until the Erie Canal was built and opened in 1825. That was a game changer. Prior to the construction of the Erie Canal, most of the United States population remained pinned between the Atlantic Ocean to the east and the Appalachian Mountains to the west. By providing a direct water route to the Midwest, the canal triggered large-scale emigration to the sparsely populated frontiers of western New York, Ohio, Indiana, Michigan and Illinois.

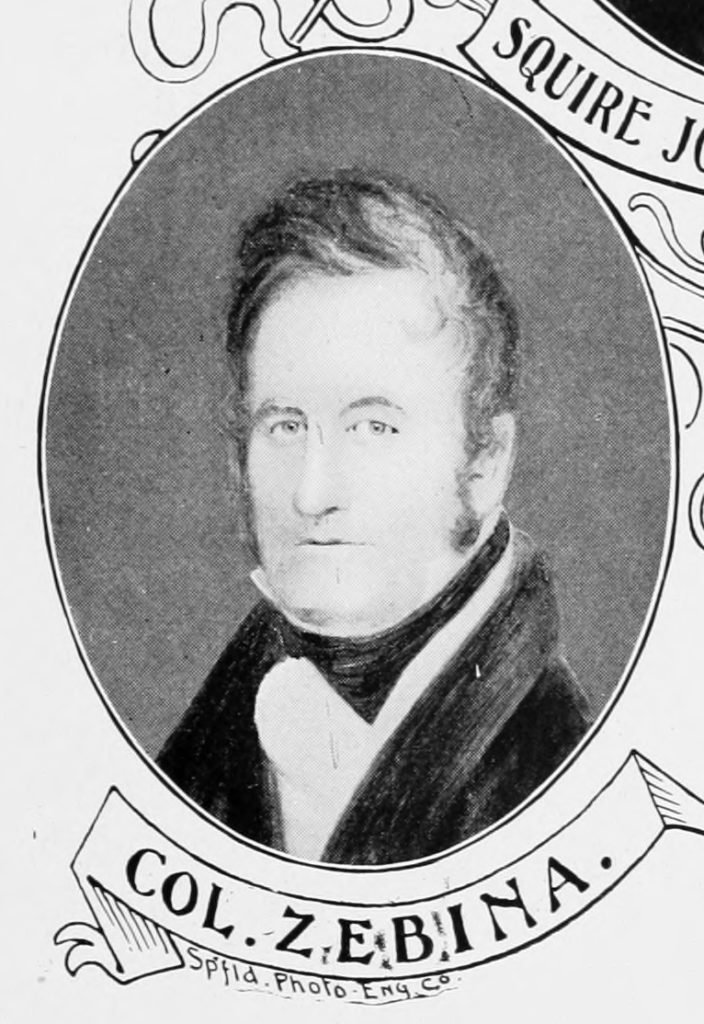

So here we have young Chester Dickinson, descended from a line of prominent Dickinsons that can be traced back to the 1600’s in the U.S. and then even further back to England (back to the 1100’s, if what I found on Geni.com is true). He was the fifth of nine children. As Alida mentions, his father, Colonel Zebina died in 1837, leaving Chester an inheritance of $7500 (which is equivalent to about $300K today). By the time Chester was 26 in 1846, 4 of his siblings had already died. His mother was still living (and lived to be 91, passing in 1878). An older brother, Bela Uriah, was also still living. After the Colonel died, I suspect that the family farm/property was left to the mother or the older brother (just speculation on my part).

So, what is an unmarried young man with some spare change in his pocket to do in 1846? As Alida states, he decided to “go west”, looking for opportunities (and possibly adventure).

- How did Chester get here?

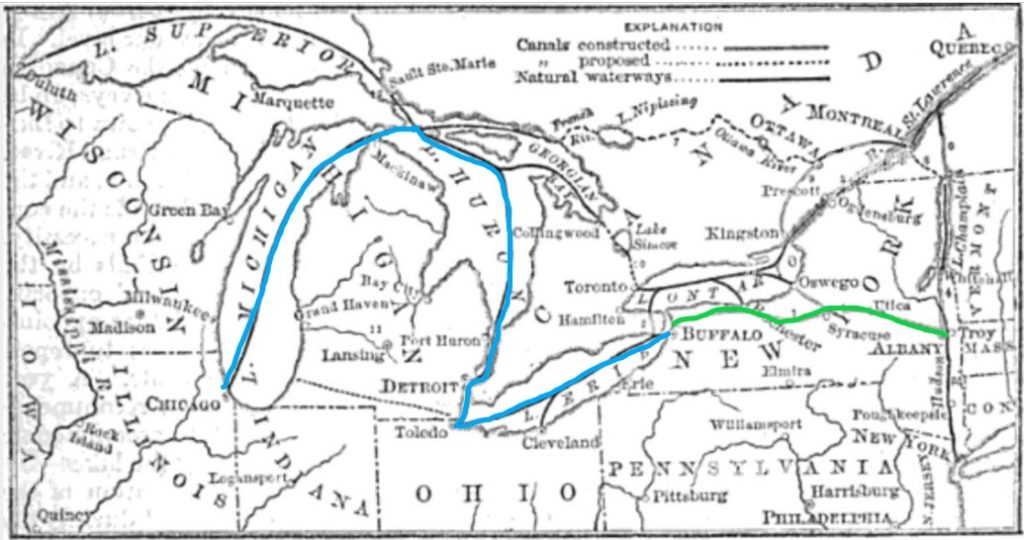

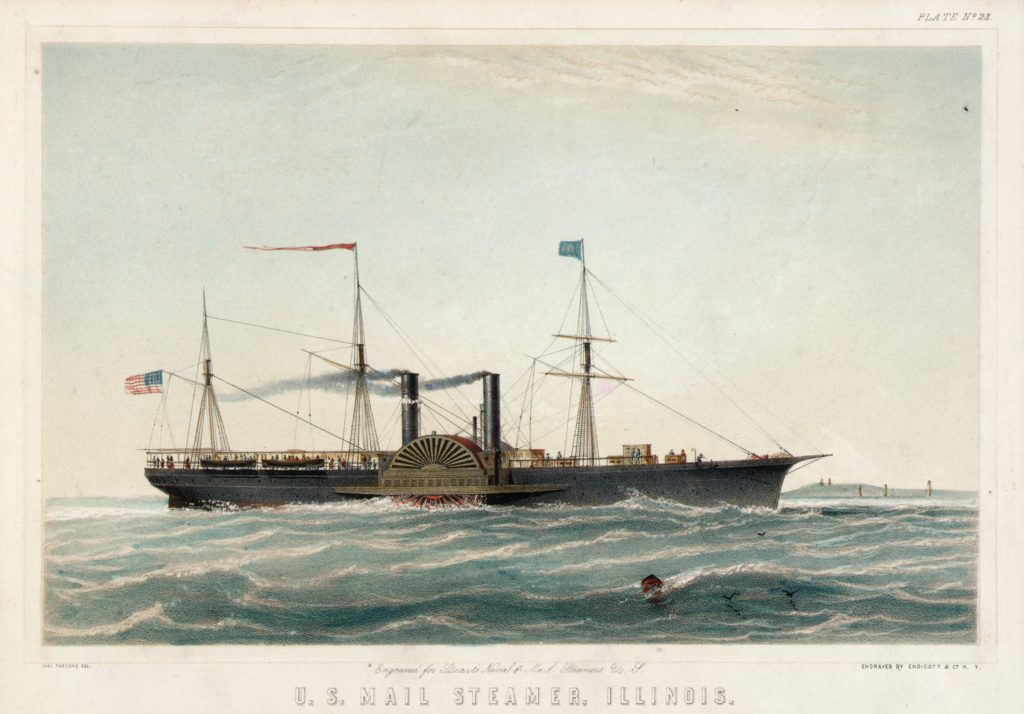

Based on Alida’s Memoirs and the Goodspeed 1909 History of Cook County, we know that Chester came to Chicago by way of the Erie Canal for the first leg of his journey, and by steamboat by way of the Great Lakes for the second leg. The original main Erie Canal ran between Albany, NY and Buffalo, NY. Amherst was only about 65 miles east of Albany, so access to the Canal was relatively convenient for Chester. The Canal journey ended at Buffalo. Steamboats were then boarded which sailed west across Lake Erie up to Detroit, then north up through Lake Huron, then across to Lake Michigan, and finally, south to Chicago – a total of about 1000 miles. Though the journey via the Great Lakes seems like it was much longer than an overland journey from Toledo or Detroit to Chicago, travelling by land was very unpleasant and, surprisingly, more expensive.

- What was the journey like? And how long did it take?

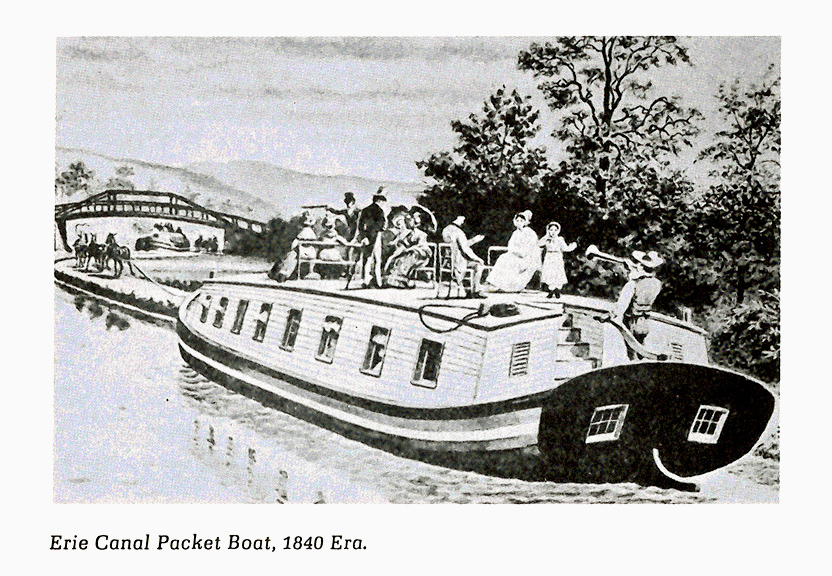

The Erie Canal supported both freight traffic and passenger traffic. Passenger boats on the Canal were called packet boats and had the right of way over the freight traffic. Packet boats came in different sizes, but the most common size was 60-80 feet long by just over 14 feet wide (to be able to fit in the locks – 72 of them!). All featured the same basic accommodations: a multipurpose room which served as lounge, dining room, and sleeping room (with a curtain to separate the ladies and men), and a kitchen. Boats were pulled by 3 horses or mules who walked along a towpath, with the team replaced about every 15 miles. Travelling at an average of 4 miles per hour, including at night, the journey from Albany to Buffalo took about 5 days. The average charge for traveling on packet boats was originally 4 cents per mile (363 miles @ $.04 = $14.52), and included meals and sleeping accommodations, but by 1846, the trip cost dropped to $7.75 with meals, and $5.75 without.

The packet boat could accommodate 60 passengers, but sometimes up to 100 and a crew of 7: a captain, 2 helmsmen, 1 bowsman, a steward, a cabin boy, and a cook.

During the day, some passengers remained on the boat’s deck, which was quite small, but most often on the roof, though they had to duck when passing under a bridge. At night, travelers slept in the cabin. It was not a pleasant place to stay. The lower straw-padded bunks were often dirty and smelled bad. Two additional tiers of upper berths were basically hammocks. Each cabin’s door and windows were closed to keep out mosquitoes, which made the cabin very hot. On the other hand, with no motor or engine sounds, the journey was very quiet.

Charles Dickens experienced packet boat travel during a visit to the U.S. in 1842 and described his experience:

“it was somewhat embarrassing at first… to have to duck nimbly every few minutes whenever the man at the helm cried Bridge and sometimes, when the cry was Low Bridge to lie down nearly flat. But custom familiarizes one to anything, and there were so many bridges that it took a very short time to get used to this.”

“…As it continued to rain most perseveringly, we all remained below: the damp gentlemen round the stove, gradually becoming mildewed by the action of the fire; and the dry gentlemen lying at full length upon the seats, or slumbering uneasily with their faces on the tables, or walking up and down the cabin, which it was barely possible for a man of the middle height to do, without making bald places on his head by scraping it against the roof.”

“….Going below, I found suspended on either side of the cabin, three long tiers of hanging bookshelves… I descried on each shelf a sort of microscopic sheet and blanket; then I began dimly to comprehend that the passengers were the library, and that they were to be arranged edge-wise, on these shelves, till morning.”

“The washing accommodations were primitive. There was a tin ladle chained to the deck with which every gentleman who thought it was necessary to cleanse himself (many were superior to this weakness), fishing the dirty water out of the canal, and poured it into a tin basin, secured in a like manner.”

“At eight o’clock, the shelves being taken down and put away and the tables joined together, everybody sat down to the tea, coffee, bread, butter, salmon, shad, liver, steak, potatoes, pickles, ham, chops, black-puddings, and sausages…”

“And yet despite these oddities… there was much in this bode of travelling which I heartily enjoyed at the time, and look back upon with great pleasure.”

At this point, I need to take a pause and confess that I am an avid fan of the British canal boat shows on streaming TV (Prime Video) and YouTube. My favorite is the delightfully boring Cruising the Cut, where nothing really happens but it is described in detail. The point of this comment is that the modern wide beam canal boats are still basically the same size as the 19th century packet boats, and seeing the interior space of these modern boats, I simply cannot imagine how 60+ people could be crammed inside a packet boat. Really, I can’t. They must have been packed in like sardines. And where was the luggage stored? And how about the crew – where did they sleep?

For more detailed descriptions of the packet boats and journey, please see the additional links at the bottom of this page, or click this link: Erie Canal – Packet Boat Stories

As far as the steamboat journey via the Great Lakes, the cabin fare in 1847 was $10 and the journey took about 5 days. Steamboat travel on the Great Lakes was not without risks – violent weather or boiler explosions being the most common hazards.

summary of the journey

Amherst to Albany – overland, cost unknown, estimated 1-2 days (maybe Chester got a ride from a relative)

Albany to Buffalo – via Erie Canal packet boat, $7.75, 5 days

Buffalo to Chicago – via Great Lakes steamboat cabin, $10.00, 5 days (steerage was much cheaper)

Possible layovers in Albany and Buffalo – 1-2 days each

Estimated total duration of the journey: 12-16 days

Total cost of boat fares; $17.75 ($690.00 today)

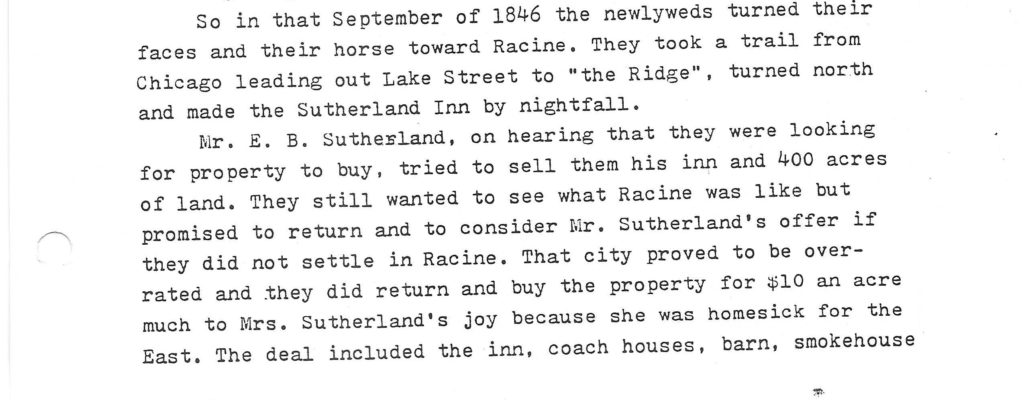

- Why did Chester settle in Jefferson?

This question is answered in Alida’s Memoirs: The original plan was to check out Racine, WI, but when that did not pan out, Chester and Alida returned to what later became the town of Jefferson to take EB Sutherland up on his offer to buy the Sutherland Inn and the land (more about this in a future article).

Or, maybe Chester had an entirely different original plan with a different destination altogether — that is, until he met and fell in love with Alida, who was headed to Joliet, IL. Maybe.

Further reading

There is no shortage of websites, articles, videos, etc. related to the history of the Erie Canal and steamboats in the 19th century. Below are just a few sites.

- The Erie Canal

- Erie Canalway National Heritage Corridor : History and Culture

- Erie Canal – Packet Boat Stories – Descriptions of what the journey was like in packet boats on the Erie Canal.

- Erie Canal (mcgill.ca)

- Erie Canal – Wikipedia

- Taking the packet | Historical Landscapes of the Erie Canal (steveboerner.com)

- Hawthorne — The Canal Boat (eriecanal.org) – Nathaniel Hawthorne’s account of his Erie Canal journey in 1835

- How’d they get here? – early Erie Canal images | Clark House Historian (jchmhistorian.com) – Erie Canal

- How’d they get here? – Steamboats! | Clark House Historian (jchmhistorian.com) – Steamboats

- Charles Dickens Steamboat Trip on the Ohio River (charlesdickenspage.com) – Charles Dickens’ account of his steamboat travels in America in 1842

Very cool. Thanks for all of your hard work on this Ruta!

Very interesting!!

Great article, Ruta! Very interesting. For those who may be interested one can ride an exact replica of a canal boat pulled by a team of mules in LaSalle, Illinois (about two hours west of Chicago) on the Illinois Michigan Canal (built roughly 1835). It opened up the Midwest and allowed grain (among other things) to be shipped to Chicago and thus started the Board of Trade. It also allowed goods to be moved up / down the country from North / South to Chicago and the Great Lakes – the rapids at Ottawa, IL prevented shipping from moving up into Chicago but the canal circumvented the rapids.

Wow, thanks for sharing that John. I think I see a field trip in the works next summer. That would be a blast with a group of neighbors.

Hi Ruta. The song “The Erie Canal” brought back many memories for me. I was born in Buffalo, NY. When I was about 3 years old my dad bought a grape farm near Silver Creek, NY. We drove across the Erie Canal to get back to Buffalo to visit friends. We were taught a lot about the Erie Canal in school. During that time I learned the whole song. I had not thought about it for MANY years! My sister and I sang it a lot as kids.

Hi Mary Ann, it’s awesome that you have such a strong connection to the Erie Canal. It was so interesting to work on the research about it. I’d love to take a trip down the canal someday.

Thanks for sharing!